It's alright, I'm also wasting my life

It's alright, I'm also wasting my life

It shouldn’t be much of a surprise that I play a lot of games. While there are a few genres that I generally like, and a few that are less my cup of tea, in general I’m pretty open to playing anything that has a good premise in either its gameplay or story. Even when I’ve given something a go and found that it isn’t my thing, there’s usually a few aspects of it that I do enjoy, or think had potential that unfortunately wasn’t tapped enough.

As you can probably tell by the title of this post, as a result of this I’m not opposed to playing older games. I wouldn’t classify myself as a retro gamer, but I’m definitely not turned off by the idea of pixel graphics or jagged models, and if something that’s old has something notable about it, I’ll happily give it a go just as easily as I would something modern. Hell, there are plenty of older games that I’ve played that are far, far better than some of the tripe that comes out today. Who would have thought that when you focus on making an enjoyable experience that makes the most of the medium rather than trying to suck as much money out of people as possible, it tends to be a more memorable and better experience?

Fun aside, there are also some nice side benefits that arise naturally when you play older games. Something that I always find fascinating that’s true of pretty much any genre or medium is that there’s always a bit of a learning period for the pioneers of it. You start off with a basic concept, and explore what you can with it. Once you’ve done that, someone else comes along and looks at another aspect of it, and then someone else does the same. Someone else tries making a rip-off of your work, and maybe they bring something new to the table, or maybe they show why something doesn’t work.

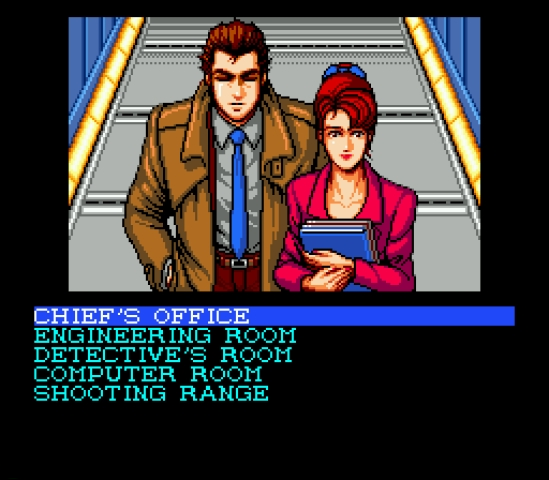

To use a real-world example, I first played the classic Hideo Kojima visual novel Snatcher last year. Visual novels are a pretty basic concept - you click, you read, you advance the story. Some - such as this one - have interactivity, and you need to actively work and solve puzzles to advance the story. In Snatcher’s case, each screen had a list of options you could choose from. The options were usually the same for each screen, with a few context-specific choices. As you progress through the game, you’ll need to use most options available to progress the story - looking at items, talking to people, interacting with devices, and so on and so forth.

This all sounds pretty basic, and it is, but here’s the thing - in spite of how basic Snatcher’s gameplay is, I learned a lot from it. Seeing a list of options explicitly listed out for me on each screen got me thinking about how I would program something similar, and how it could allow for more interactivity in a visual novel than just clicking forwards and occasionally receiving a choice to make. I’m sure that there are plenty of visual novels that do something similar - I’ve probably played some of them and just can’t recall what they were - but a lot fall back on just clicking and reading, which can have its downsides and flaws.

Simultaneously, the presentation and gameplay showed me a few flaws that I’d want to avoid. Sometimes the gameplay of Snatcher can be a bit clunky - you often have to look at something before you can investigate it, and sometimes investigating something will then give you something new to look at, which you won’t always realise. Why not just consolidate the look and investigate options into a single choice? The presentation also involved scrolling through menu options for the majority of the time, and while it was probably just a necessity of the way things worked back then, it was a bit slower than I’d have liked. I probably wouldn’t have considered doing either of these things anyway, but getting to try them out helps to quash the idea before I try it, and shows why they don’t work as well as the alternatives.

There’s something else that I like about seeing failed or weak concepts - they can also give inspiration. Sometimes you’ll see an idea that doesn’t really work as it is, but you can see that with a little bit of tweaking it will be something really interesting, or at the very least not painful. For example, I played Metal Gear 2 for the first time last year, and there’s a section where you have to wander through a swamp. The path you take isn’t visible, and if you wander off it you risk drowning, so it’s pretty much a slow, trial-and-error sequence that isn’t any fun to play. There’s a simple fix for it, though - if there was an optional map, or item to reveal the path, then that would add a bit of content to the game. It wouldn’t be cited as the most interesting part of the game or anything, but it would help to fix a bad sequence, and could be reused somewhere else later. Hell, maybe you could stop enemies by luring them into the swamp or something - that would be much more interesting than the sequence as it is.

Even if you think that you know everything about a classic game, just through its reputation and references to it in the industry, there’s still a lot that you can learn and appreciate from playing it yourself. There’ll be parts of a game that people don’t bring up much which might turn out to be your favourite aspect of it, or more interesting than you originally gave it credit for. As a general example, a lot of fans of the Thief series are fairly dismissive of the third game, Deadly Shadows, for eschewing large, non-linear levels in favour of smaller levels with areas broken up by loading screens. If I’d listened to its reputation I’d have never gotten to play the game, but it’s actually my favourite of the series, with lots of things that people never talk about - a mysterious hidden city full of Lovecraftian fish-like people, an excellent prophecy twist caused by a literal interpretation of a statement, sneaking into the locked up compound of your former allies, and a really fun museum heist to top things off. I’ve definitely played games which have lived up to a poor reputation (looking at you, Devil May Cry 2), but I’ve played just as many which have surprised me with how enjoyable they’ve been.

For another example, I recently started playing Silent Hill 2 with some friends who had never played it before. One of them knew a major twist that happens towards the end of the game, but otherwise they were both going in blind. If they’d just thought, “Well, I know the twist; I don’t really need to play the full game,” then they would have missed out on so much. Watching these friends gasp at creepy noises in the omnipresent fog, witness the twisted designs of the monsters they encounter, or even just trying to work out a puzzle’s solution, I’m fairly certain that they’ve gotten more out of the game than if they had just skimmed a Let’s Play, or read a plot summary on the internet.

Old games can definitely be weak at times, and there are more than a few gameplay elements that we’ve moved past which I don’t miss. Even so, there are plenty of games that are hidden gems, or bonafide classics, which I feel many people are dismissing or forgetting exist. Even when they are remembered, it tends to be along the lines of, “Ah, yeah, I’ve heard this game exists and is good,” and while it is good that they’re still being remembered, it’s nothing compared to if they’re played. Whether that leads to discovering parts of them that are underrated, learning from them, or even just getting inspired by them, there are a lot of benefits to playing older games, and it’s something that I’ll probably keep doing until the day I die.

What are some older games that you still play, or are interested in playing? Are there any games that have inspired you, or have mechanics which you’d like to see fleshed out more? Let me know - in case it wasn’t obvious, I love thinking about the evolution of genre and mechanics, and how everything fits together. I’ll be keen to hear about what your thoughts are!

Back to news